For many who live in Currituck County, the Mid-Currituck Bridge (MCB) has become more urban myth than infrastructure reality.

The more skeptical among them believe they’ll see a sailboarding Sasquatch before they can drive directly across the Currituck Sound to Corolla.

And who can blame them? The MCB is a project that has picked up steam and then stalled out more times than locals can count.

Conversations about creating a new connection from the mainland to the Outer Banks started in the 1970s. Five decades later, most folks in the area have adopted an “I’ll believe it when I see it” attitude.

But there are signs that things are about to change.

Seriously.

Let’s start with a look at where things first got serious, back in a strange decade we’ll call “the 1990’s.”

In the interest of time and space, we’ll skip the bureaucratic blow-by-blow (you can read everything here) and give you an abbreviated version of the last 27 years.

In 1995, the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) published a Notice of Intent to prepare an environmental impact statement for the bridge.

The Notice of Intent was joined by a Draft Environmental Impact Statement (DEIS) in 1998. But changes in state legislation forced adjustments and caused delays for a decade. Activity picked back up in 2008.

The NC Turnpike Authority (NCTA) completed a new DEIS in March of 2010. Less than two years later, it delivered the Final Environmental Impact Statement (FEIS).

All those acronyms and reports really made things feel like they were moving forward. The NCTA even established a public-private partnership to begin construction. But the private developer could never reach an agreement with the department in terms of the cost for actually building and maintaining the facility.

NCTA terminated the partnership.

In the years that followed, the MCB project more or less sat idle. But the notion of a shortcut to the Currituck Outer Banks haunted conversations like rumors of a ghost ship cruising off the coast of Corolla. People wanted to talk about it, but were quick to curb their enthusiasm.

It felt like every year officials announced some kind of new setback or delay.

But in 2019, the project took a giant leap towards the starting line, when the Record of Decision (ROD) arrived.

What’s an ROD? According to Wikipedia, a “ROD issued by the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) signals formal federal approval of an Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) or Environmental Assessment (EA) concerning a proposed highway project. The ROD authorizes the respective state transportation agency to proceed with design, land acquisition, and construction based on the availability of funds.”

When you’re trying to build something big, a bright green light from the federal government is a good thing.

Bridge supporters could almost see the light at the end of the tunnel.

But with their eyes temporarily blinded by that light, they missed a one-two punch that managed to set them back just a little bit longer.

First came the lawsuit.

In April 2019, the Southern Environmental Law Center (SELC) filed a suit on behalf of the North Carolina Wildlife Federation and No Mid-Currituck Bridge, a group of mainland Currituck County and Outer Banks residents who are opposed to the bridge.

Bridge proponents weren’t exactly surprised. Legal action from opponents of large development projects is fairly common.

But the second punch? The global pandemic? That was a little more unexpected.

COVID shut down the MCB’s momentum just like it shut everything else down. Coping with the pandemic put a crunch on the NCDOT budget, forcing the department to put some “in-development” projects on hold.

But as the state recovered and COVID cases dropped, supporters of the MCB once again watched and waited for signs of life.

In the meantime, people came to vacation in the Outer Banks in record numbers. Home construction and population numbers ramped up in Currituck County. And communities like Southern Shores and Duck grew more frustrated by bumper-to-bumper seasonal traffic.

Then something big happened.

On December 13, 2021, U.S. District Judge Louise Wood Flanagan ruled in favor of the N.C. Department of Transportation (NCDOT) and the Federal Highway Commission, clearing the way for the bridge’s construction.

As expected, the SELC has filed an appeal. But supporters of the bridge are excited to finally have some open road and the ability to “step on the gas” and move the project forward.

During a Currituck County Board of Commissioners retreat in January 2022, former BOC chairman and current state Rep. Bobby Hanig (R-Currituck) didn’t mince words.

“They are building the bridge,’ he said. “It is going to happen.”

Initially, Hanig announced that construction would begin in 2023. He later corrected himself after hearing from NCDOT that the start of construction would be closer to 2025.

So in this case, “stepping on the gas” might not be the most accurate analogy. The MCB isn’t going to break any landspeed records. But, for now, things are definitely moving forward.

Another good sign? An NCDOT map lists the MCB construction year as “2024.”

According to those who have been following this project closely, that sort of “official” labeling has never happened before.

What does “moving forward” mean exactly?

Great question.

That’s why we asked people who would most likely know the answer.

Our first call was to HW Lochner, the engineering firm working as consultants on the project. The big idea was to talk about HOW the bridge would get built and what Currituck could expect in terms of the construction process and the overall design of the MCB.

Now that the question of “Will it happen?” has been answered, it seems only logical to wonder what the bridge will look like.

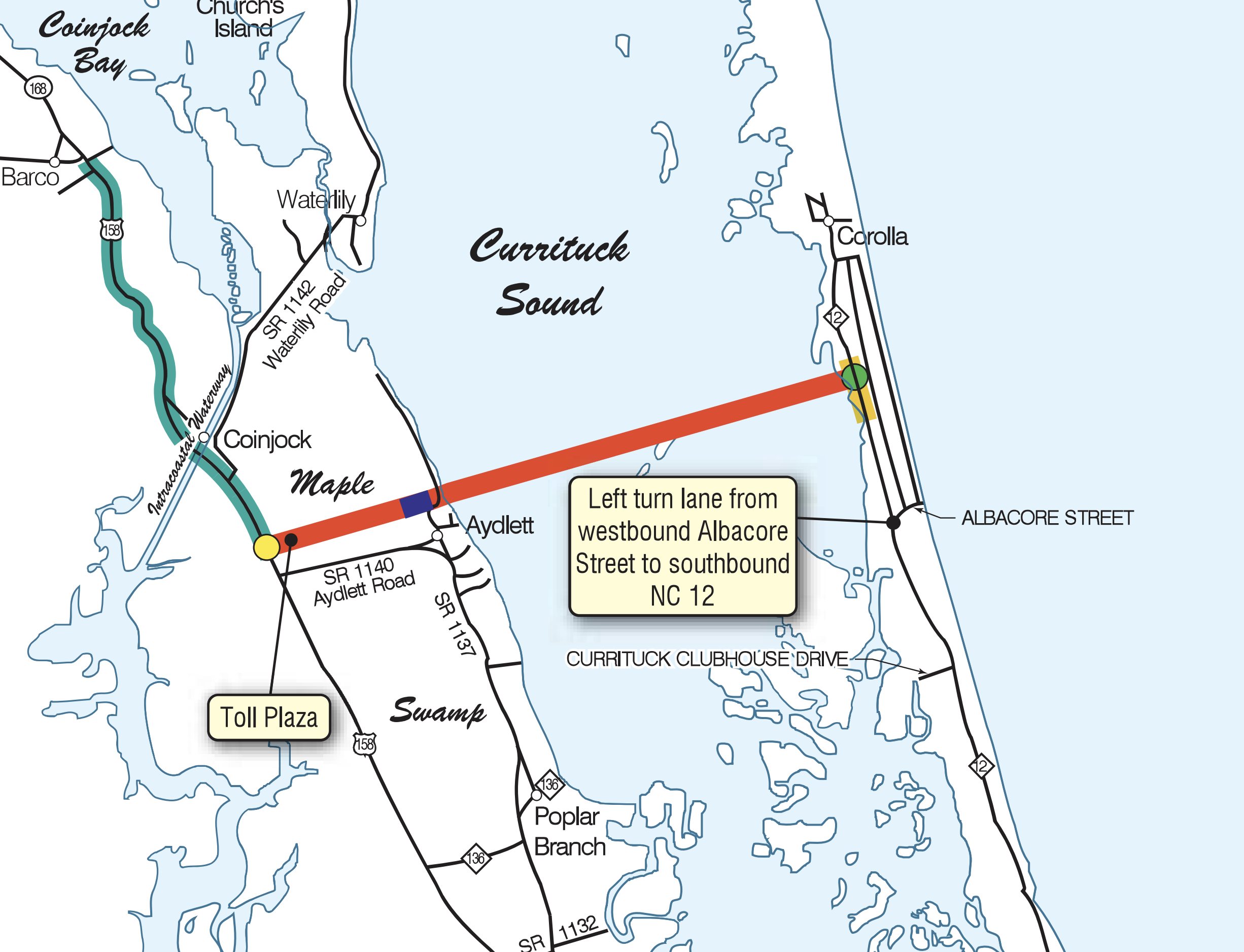

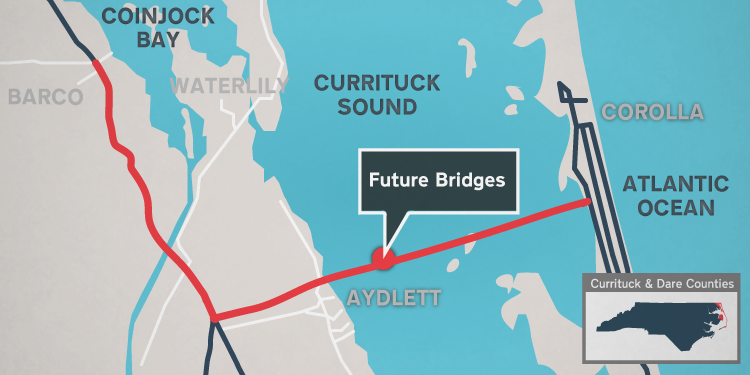

For years, the only “official” representation of the MCB was a thick red line running across the light blue of the Currituck Sound on a PDF map.

It seemed like a cool idea to ask the bridge builders to discuss the physical structure that would actually exist in the real world.

Maybe they could share concept drawings or 3D animations. Best case scenario? A personal tour of the sprawling scale model.

But here’s the thing, none of those exist yet.

That’s because one of the biggest pieces of the MCB puzzle has yet to fall into place: the awarding of the construction contract. The NC Turnpike Authority still needs to pick the construction company that is going to build the bridge and that company still needs to select the engineering firm to design it.

For now, the MCB remains a fat red line on a map.

But not for much longer.

In the meantime, here are highlights from a discussion with Roy Bruce, PE (Senior Transportation Project Manager at HW Lochner), Jennifer Harris, PE (General Engineering Consultant with the North Carolina Turnpike Authority) and Rodger Rochelle, PE (former Chief Engineer for the North Carolina Turnpike Authority).

How do you go about deciding where the bridge goes?

Roy Bruce: The first thing to understand is that the project needs to fit into its setting. You're looking at a number of different constraints that might prohibit putting a road or bridge in a certain location. And so, you map all of those constraints and begin to look for opportunities to physically locate the road and bridge.

You're never going to be able to locate a facility that has absolutely no constraints associated with it and no impacts. It becomes a balancing act between what the needs of the project are and what the environmental or social or human constraints are that dictate location.

In an area like the Outer Banks, you have limited physical locations. That’s one constraint.

What were some of the specific factors that led you to the location?

Roy: It may seem like the mainland has a lot of open fields and farmland, and that it should be easy to locate a road and bridge there. But [mainland Currituck County] is really a pretty narrow strip of land. Because we need to put an interchange and a toll plaza in at US 158, we were limited by the availability of land.

We looked at all of the different options and summarized the impacts associated with each. We asked what were the pros and cons of each alternative location?

How long did that whole process take?

Roy: It took some time to examine all reasonable alternatives. There's not only the engineering study that goes into all of those alignments, but then there's also a public involvement process that goes along with it. So NCTA took public comments and evaluated those comments about whether the bridge should be located at a southern alignment, northern alignment or a sort of middle alignment. NCTA ended up with a middle alignment.

Jennifer Harris, PE: There are a lot of environmental agencies that we coordinate with and ultimately have to get permits from in order to construct the project. So they had a lot of input into the process over the years as well.

Rodger Rochelle, PE: The environmental features are a key component. We’re in an alignment that crosses Maple Swamp, which is a “pre-harmed area,” if you will, largely deforested. So the impacts aren't as great by taking that alignment. But we have to worry about subaquatic vegetation and all these environments, whether they be streams or wetlands or subaquatic vegetation or species habitat. Each of them has to be surveyed in detail in order to understand the impacts, or potential impacts. It takes time to do all that.

Is the length of time the MCB has been in process fairly typical?

Rodger: I would say it's not typical. Some other large projects, particularly bridges in areas like the Outer Banks, for instance, the Oregon Inlet Bridge (the Bonner Bridge replacement) took quite some time to get through.

Wright Memorial Bridge

Wright Memorial Bridge

What kind of bridge will it likely be?

Roy: More than likely it will be a bridge that has piles driven into the ground for the substructure, and then beams set on top of a cap on top of those piles and a deck constructed on top of the beams, pretty much like the Wright Memorial Bridge, or the US 64 bridge down to Manteo.

Those are pretty typical bridges, given the subsurface conditions of the area. It's unlikely that you would see a very long span, segmental type bridge at this location because of a variety of factors, but that's yet to be determined too, because ultimately there will be a final bridge design. But given the conditions right now, more than likely, it's going to be piles with a cap and beams supporting a deck.

Jennifer: There will be two travel lanes on the bridge... one lane in each direction, with shoulders.

Roy: The subsurface conditions are such that friction piles will work for this bridge. They may have to be pretty long because of the sandy, silty kinds of materials into which they are being driven. Part of the engineering challenge will be finding that sweet spot between what's the best length of each span and length of the piles to support the bridge. Looking at the efficiency of span length and pile length is what’s going to be important for this bridge.

The piles would be driven in. We've already done geotechnical investigations. There may be some other geotechnical investigations done in Currituck Sound and Maple Swamp for the final design, the contractor may elect to actually drive some piles and test them to see what kind of load they can support so that this information can help with their design. But we have pretty good information across the Currituck Sound and Maple Swamp right now on what we think is going to be needed.

I really don't think it's going to be all that different from the bridges to the south. And the Wright Memorial bridge is older, but it's still the same type of bridge.

RELATED READ: A Guide to the Bridges of the Outer Banks

Are there any developments that have come along that will improve the construction or durability of the bridge?

Roy: Certainly beam design has evolved since the Wright Memorial Bridge was built, which allows for longer concrete beams to carry greater loads. That will help with some of the efficiency because there's going to be a lot of money spent on the piles that are actually driven into the ground that nobody's going to see. If the designers can make those spans longer, it helps reduce the number of piles that the contractor is driving into the ground to get friction to hold up the bridge.

Bonner Bridge

Bonner Bridge

Rodger: We've learned an awful lot about concrete durability over the last few decades. And we employed that on Bonner Bridge, which exists in a more corrosive environment than [the MCB]. We specified stainless reinforcing steel in all the concrete, or most of the concrete, at Bonner Bridge.

Chemical admixtures were added to the concrete to improve durability. And some of those features will be employed. We anticipate that when we build a bridge now, it will last a lot longer and require less maintenance than when we built bridges 30 years ago.

Typically for a bridge like this, we would specify concrete that would last a hundred years.

Jennifer: I think something that sets this project apart from others is the length. The bridge over Currituck Sound is 4.7 miles long. But That's pretty unique compared to some of those other bridges that have been discussed.

Roy: That is true. It's longer than the other bridges in the area.

So is it going to be two different bridges?

Roy: Well, the Maple Swamp bridge is a mile and a half. There's a half-mile section of roadway separating the two bridges. This segment of highway will be in Aydlett. You won't be able to access the facility at Aydlett, but it will pass through the area.

Rodger: We don't anticipate this to be a dramatic looking bridge by any means. It's got to be much lower than Oregon Inlet. And because we don't have the navigation requirements at this location that we do at Oregon Inlet. It won't be nearly as tall.

We work with the US Coast Guard and send out surveys to local marinas, boat owners, and other entities asking them what their travel patterns are and what their needs are. And then the US Coast Guard makes a predetermination from all those survey responses about what the length of that navigation zone as we call it needs to be and what the height needs to be.

Roy: They also take into consideration other structures across the waterway, such as the Wright Memorial Bridge and what the existing opening is at the Wright Memorial Bridge. And Currituck Sound does not include the intracoastal waterway, so there is not a lot of large vessel traffic going up and down the Sound. A lot of it is recreational boats or small commercial fishing vessels.

It's very shallow in some places and probably the deepest Currituck Sound gets is about 10 feet.

In terms of the process, if we can get to the point where everything is green-lit and things are rolling along, what can people expect in terms of the process of construction?

Roy: The bridge constructor will start with the pile installation. That'll be the first thing folks will see. It will look like sticks coming out of the water. But there'll be concrete or steel sticks. And then you'll see them set the cap on top of the piles, and then start the beam installation on top of that.

On the roadway portion, citizens will see the contractor start moving dirt for building up any embankments that need to be built for the interchange area or for the approach area to the bridge itself.

Rodger: This is anticipated to be a design-build contract, which means the contractor hires their qualified and pre-approved designer to do the final design of the structure.

After we award a contract, there will be a period of time where there doesn't appear to be any activity in the field. And that's because they're doing the final design and getting any permit modification they need. Having that final design approved by NCDOT, and the Turnpike Authority. That can take from several months up to a year before construction would actually start after the contracts were awarded.

Jennifer: After the design-build contract is awarded, construction work would likely start a year, to a year and a half later.

Roy: People will probably see work in Maple Swamp before they see activity in Currituck Sound. There'll be some clearing of vegetation in the Maple Swamp. That would an early construction activity.

There are some environmental constraints on construction because of protections for various fish species that will limit the time when pile driving can be done in certain areas of Currituck Sound. Where there is subaquatic vegetation, pile driving in that area will be limited more to the winter months. So activity may shift during construction to different parts of the project, depending on what's allowed at certain times of the year.

I want to note that what I've described for the bridge and bridge elements is our current thinking. As Rodger said, this will likely be a design-build contract.

The design-build team will actually bring their ideas and design to the bridge. If they view this differently than we're viewing it, that's part of the design-build process. They may bring some innovation, new ideas and techniques to the table that saves money in the building process of the bridge.

RELATED READ

INFOGRAPHIC: What You Need to Know

About the Mid-Currituck Bridge

So is HW Lochner working as a sort of a project coordinator?

Rodger: Yes, and for clarity, HW Lochner cannot pursue the construction design-build contract. They cannot be involved because they are representing us.

Jennifer: There are also a number of environmental commitments that were part of the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) document that set boundaries to ensure that those things that we're committed to from a minimizing environmental impact standpoint are memorialized and get carried forward into the construction phase of the project. And there may be more commitments or conditions that come out of the permitting process.

How do hurricanes and strong coastal storms factor into the planning?

Roy: I was just going to comment that we have done coastal ecological investigations, looking at various different paths for hurricanes and what would be the worst case scenario for the Currituck Sound and taking into consideration what that potentially could do and how to build this bridge so that it can withstand that storm.

The significant storm is one that would come up through the mainland pushing water into Currituck Sound. And it's not so much the water being pushed up into the sound. It's the water coming back down the Sound after the hurricane passes.

That water actually produces a lot of scour or eroding of the soils around those piles to the bridge. And so that has to be taken into consideration when you're designing the pile lengths and how much of that friction you can get from each of those piles.

Rodger: And I will add the bridge’s structures are designed for different wind speeds, depending on where you're located, just like they would be designed differently for earthquakes based on whatever seismic zone you're located in.

Obviously the closer you get to the coast, the higher the wind speed that we need to use. We have to consider wave height and wave action. And in some cases, even think about what if a barge broke loose and hit the bridge? Can it withstand that?

Is there anything concrete we can say about when the bridge will start in earnest, or when the final product will be open for traffic?

Jennifer: The design-build procurement process will take some time to get a team on board and then purchase right of way (property) that we need to build the project.

Rodger: We at DOT in particular, the Turnpike Authority, never think of a schedule in a linear manner. We’re always looking for ways to intermingle or overlap activities where we can. So we're certainly going to be doing that once we ramp up a little closer to the design-build contract.

We had long conversations ever since the challenge was filed about the things that we can do while we wait to make sure that we've accelerated the project as much as we can once we have a ruling.

That's the kind of stuff that we've been doing. The public doesn't see it, but it's been happening.

These Stories on Mid Currituck Bridge

No Comments Yet

Let us know what you think